Introduction

Molar mass is one of the most important concepts in quantitative chemistry. It forms the critical link between the microscopic world of atoms and molecules and the macroscopic world of grams and kilograms. While Lecture 2 focused on the mole and Avogadro’s number, this lecture expands on how to calculate the molar mass of elements and compounds, and how to apply it in chemical calculations.

Understanding molar mass allows chemists to:

- Calculate the amount of substance required for reactions

- Determine the number of particles in a given mass of material

- Predict yields in chemical synthesis

- Prepare solutions with precise concentrations

This lecture covers:

- Definition of molar mass and units

- Calculating the molar mass of elements and compounds

- Practical applications in the laboratory and industry

- Step-by-step examples of molar mass calculations

- Linking molar mass to mass-mole conversions

- Common pitfalls and tips for accuracy

1. Definition of Molar Mass

Molar mass (M) is defined as the mass of one mole of a substance, expressed in grams per mole (g/mol).

- For elements, the molar mass is numerically equal to the relative atomic mass on the periodic table.

- For compounds, it is the sum of the molar masses of all atoms in the chemical formula.

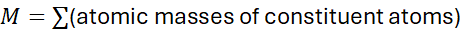

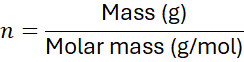

Formula:

Units: grams per mole (g/mol)

Example:

- Oxygen (O) = 16 g/mol

- Hydrogen (H) = 1 g/mol

- Water (H₂O) = 16 + (2 × 1) = 18 g/mol

Further Reading: Royal Society of Chemistry – Periodic Table

2. Calculating Molar Mass

2.1 Elements

For a single element, the molar mass is simply the relative atomic mass from the periodic table.

Example:

- Carbon (C) = 12.01 g/mol

- Sulphur (S) = 32.06 g/mol

2.2 Compounds

For compounds, multiply the atomic mass of each element by the number of atoms present in the formula and sum the results.

Example:

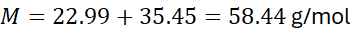

- Sodium chloride (NaCl):

- Sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄):

2.3 Hydrated Compounds

Some compounds contain water of crystallisation. Include the mass of water in the molar mass calculation.

Example:

- Copper(II) sulphate pentahydrate, CuSO₄·5H₂O:

3. Practical Applications of Molar Mass

3.1 Laboratory Calculations

- Determining the mass of reactants required for reactions

- Preparing solutions of specific concentrations

- Calculating product yields from reactions

Example: Preparing 0.5 M NaOH solution:

- Required: 0.5 moles per litre

- Molar mass NaOH = 39.99 + 15.999 + 1.008 = 56.997 ≈ 57 g/mol

- Mass required for 1 litre: 0.5 × 57 = 28.5 g

3.2 Industrial Applications

- Large-scale synthesis of chemicals requires precise mass calculations

- Pharmaceuticals: ensuring accurate dosage of active ingredients

- Material science: calculating required quantities of polymers or alloys

4. Step-by-Step Worked Examples

Example 1: Molar Mass of Glucose

Problem: Calculate the molar mass of C₆H₁₂O₆.

Solution:

- Carbon: 12 g/mol

- Hydrogen: 1 g/mol

- Oxygen: 16 g/mol

- Total: 12 + (1 × number of H atoms) + 16 = depends on the formula

Conclusion: Molar mass of glucose = 180.16 g/mol

Example 2: Molar Mass of Magnesium Hydroxide

Problem: Mg(OH)₂

Solution:

- Mg = 24.31 g/mol

- O = 16.00 × 2 = 32.00 g/mol

- H = 1.008 × 2 = 2.016 g/mol

- Total: 24.31 + 32.00 + 2.016 ≈ 58.33 g/mol

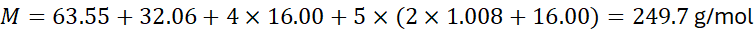

Example 3: Hydrated Salt – Copper(II) Sulphate Pentahydrate

Problem: CuSO₄·5H₂O

Solution:

- Cu = 63.55 g/mol

- S = 32.06 g/mol

- O₄ = 64.00 g/mol

- 5H₂O = 5 × 18.016 = 90.08 g/mol

- Total = 63.55 + 32.06 + 64.00 + 90.08 ≈ 249.69 g/mol

Example 4: Mixture of Compounds

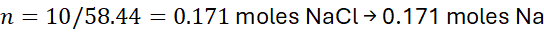

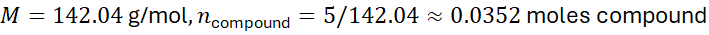

Problem: A sample contains 10 g of NaCl and 5 g of Na₂SO₄. Calculate the total moles of sodium.

Solution:

- Moles of Na in NaCl:

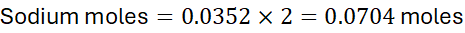

- Moles of Na in Na₂SO₄:

- Total moles of Na = 0.171 + 0.0704 ≈ 0.2414 moles

5. Linking Molar Mass to Mass-Mole Conversions

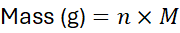

Molar mass is the key factor in converting mass to moles and vice versa. The general formula:

Example 5: Mass of Water

Problem: Find the mass of 0.25 moles of H₂O.

Solution:

- Molar mass H₂O = 18 g/mol

- Mass = 0.25 × 18 = 4.5 g

Example 6: Moles in Sodium Carbonate

Problem: How many moles are in 105 g of Na₂CO₃?

Solution:

- Molar mass = 22.99×2 + 12.00 + 16×3 = 105.98 g/mol

- Moles = 105 / 105.98 ≈ 0.991 moles

6. Common Pitfalls

- Ignoring significant figures: Always report mass and molar mass to appropriate precision.

- Hydrates and water of crystallisation: Remember to include water molecules in molar mass calculations.

- Mixtures of compounds: Break down each compound separately when calculating total moles or mass.

- Unit consistency: Always use grams for mass and g/mol for molar mass.

7. Practical Tips

- Create a stepwise plan: identify elements, count atoms, multiply by atomic masses, and sum.

- Use a periodic table with decimals for atomic masses.

- Double-check hydrated compounds and polyatomic ions.

- For mixtures, treat each compound separately before combining results.

Further Reading:

Conclusion

Molar mass is more than a number; it is the essential conversion factor that links moles to grams. By mastering molar mass calculations, students can:

- Accurately convert between mass, moles, and particles

- Calculate required reactant quantities and product yields

- Prepare solutions of the desired concentration

- Solve complex stoichiometry problems

Subsequent lectures will build on this knowledge to explore mass-mole conversions, solution concentrations, percentage composition, and empirical formulas, culminating in full worked examples in the final lectures.

Next Lecture (Lecture 4): Converting Between Mass and Moles – Step-by-Step Methods and Applications.

Support the Archive

This archive is freely shared as a communal act of care.

If you’d like to support its continuation, consider purchasing a companion PDF set for £1 per lecture, with an associated quiz, via Payhip, with the final price depending on the number of lectures in the set, available only once the full series is complete.

Explore more with us:

- Read our Informal Blog for relaxed insights

- Discover Deconvolution and see what’s happening

- Visit Gwenin for a curated selection of frameworks

- Browse Spiralmore collections