Introduction

The mole is one of the most fundamental concepts in chemistry, yet it is often misunderstood. It acts as a bridge between the microscopic world of atoms and molecules and the macroscopic world of grams and litres. Mastering the mole allows chemists to measure quantities accurately, predict reaction yields, and understand the relationships between different chemical species in a reaction.

This lecture will cover:

- Definition and significance of the mole

- Avogadro’s number and its historical context

- Practical applications of the mole in the laboratory and industry

- Converting between particles, moles, and mass

- Worked examples and problem-solving strategies

- Common misconceptions and pitfalls

By the end of this lecture, students will be able to apply the mole concept with confidence in calculations and experimental planning.

1. Definition of the Mole

A mole is defined as the amount of substance containing exactly 6.022 × 10²³ elementary entities (atoms, molecules, ions, or particles). This constant, known as Avogadro’s number (Nₐ), provides the link between the number of particles in a sample and the macroscopic mass of the substance.

- Elementary entities can refer to:

- Individual atoms (e.g., 1 mole of carbon atoms)

- Molecules (e.g., 1 mole of oxygen gas, O₂)

- Ions (e.g., 1 mole of Na⁺ ions)

- Formula units in ionic compounds (e.g., 1 mole of NaCl)

Importance of the mole:

- Allows chemists to count particles indirectly through mass measurements.

- Enables stoichiometric calculations in chemical reactions.

- Forms the basis for solution concentrations, empirical formulas, and yield predictions.

2. Avogadro’s Number and Its Historical Context

Avogadro’s Number (Nₐ) = 6.022 × 10²³ particles per mole.

- Named after Amedeo Avogadro (1776–1856), who first hypothesised that equal volumes of gases, at the same temperature and pressure, contain equal numbers of molecules.

- Determined experimentally through a combination of gas laws, X-ray crystallography, and electrochemical methods.

- Provides a fundamental link between the microscopic scale (atoms/molecules) and the macroscopic scale (grams/litres).

Historical Milestones:

- 1811: Avogadro’s hypothesis was proposed.

- 1865: Stanislao Cannizzaro clarified the distinction between atoms and molecules, leading to widespread acceptance of Avogadro’s ideas.

- 20th Century: Modern techniques (X-ray diffraction, electron microscopy) refined the value of Nₐ.

Why it matters today:

- Fundamental in chemical metrology for defining quantities precisely.

- Critical in industrial chemistry for scaling reactions and calculating yields.

Further Reading: Khan Academy – Avogadro’s Number

3. Practical Applications of the Mole

3.1 Laboratory Applications

- Reactant Measurements: Determine the exact mass of reactants needed to ensure complete reactions.

- Solution Preparation: Calculate the amount of solute to achieve a desired molarity.

- Gas Calculations: Use the ideal gas law with moles for volume and pressure calculations.

Example:

To prepare 1 litre of 1 M NaCl solution, 1 mole (58.44 g) of NaCl is dissolved in 1 litre of water.

3.2 Industrial Applications

- Pharmaceutical Manufacturing: Precise dosages depend on mole-based calculations.

- Material Synthesis: Nanomaterials and polymers require exact stoichiometric ratios.

- Food Chemistry: Nutrient calculations often involve molar concepts for macronutrients.

4. Converting Between Particles, Moles, and Mass

Understanding how to interconvert particles, moles, and mass is essential.

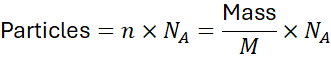

Moles relationships:Where:

- n = number of moles

- N = number of particles (atoms, molecules, ions, etc.)

- NA = AvOGADRO’s number =6.022×1023

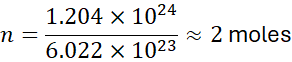

Example 1:

How many moles are in 1.204×1024 molecules of O₂?

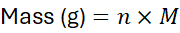

4.2 Moles ↔ Mass

Where M= molar mass in g/mol.

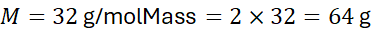

Example 2:

Mass of 2 moles of O₂:

4.3 Mass ↔ Particles

- Use moles as an intermediary:

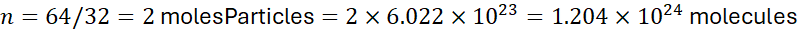

Example 3:

Number of molecules in 64 g of O₂:

5. Worked Examples: Step-by-Step

Example 4: Carbon Atoms in a Sample

Problem: How many carbon atoms are in 12 g of carbon (C)?

Solution:

- Molar mass of carbon: 12 g/mol

- Number of moles: n = mass ÷ molar mass = 12 ÷ 12 = 1 mole

- Number of atoms: N = number of moles × Avogadro’s number = 1 × 6.022 × 10²³ = 6.022 × 10²³ atoms

Conclusion: There are 6.022 × 10²³ carbon atoms in 12 g of carbon.

Example 5: Molecules in Water

Problem: How many water molecules are present in 18 g of H₂O?

Solution:

- Molar mass of H₂O = 18 g/mol

- Number of moles = mass ÷ molar mass = 18 ÷ 18 = 1 mole

- Number of molecules = number of moles × Avogadro’s number = 1 × 6.022 × 10²³ = 6.022 × 10²³ molecules

Further Reading: ChemCollective – Mole Calculations

Example 6: Particles in Sodium Chloride

Problem: How many formula units are in 29.22 g of NaCl?

Solution:

- Molar mass of NaCl = 58.44 g/mol

- Number of moles = mass ÷ molar mass = 58.44 ÷ 58.44 = 1 mole

- Number of particles (formula units) = number of moles × Avogadro’s number = 1 × 6.022 × 10²³ = 6.022 × 10²³ formula units

6. Common Misconceptions and Pitfalls

- Confusing particles with moles: A mole refers to 6.022 × 10²³ particles, not grams.

- Mixing units: Always check whether the mass is in grams and the molar mass in g/mol.

- For molecules vs. atoms: In O₂, one molecule contains two atoms, so calculations must account for molecular structure.

7. Practical Tips for Students

- Always write units in each step.

- Draw a conversion tree: Mass ↔ Moles ↔ Particles.

- Memorise Avogadro’s number and the concept of the mole.

- Use periodic table values carefully, noting significant figures.

7. Practical Tips for Students

- Always write units in each step.

- Draw a conversion tree: Mass ↔ Moles ↔ Particles.

- Memorise Avogadro’s number and the concept of the mole.

- Use periodic table values carefully, noting significant figures.

Conclusion

The mole is central to all quantitative chemistry calculations. By understanding:

- What a mole represents

- How to use Avogadro’s number

- How to convert between moles, mass, and number of particles

…students can confidently handle a wide range of chemical problems. Mastery of the mole concept will serve as the foundation for understanding molar mass, concentrations, percentage composition, empirical formulas, and stoichiometry in subsequent lectures.

Next Lecture (Lecture 3): Molar Mass – Calculation, Applications, and Complex Examples.

Support the Archive

This archive is freely shared as a communal act of care.

If you’d like to support its continuation, consider purchasing a companion PDF set for £1 per lecture, with an associated quiz, via Payhip, with the final price depending on the number of lectures in the set, available only once the full series is complete.

Explore more with us:

- Read our Informal Blog for relaxed insights

- Discover Deconvolution and see what’s happening

- Visit Gwenin for a curated selection of frameworks

- Browse Spiralmore collections